PO Box 95

Lyttelton 8841

Te Ūaka recognises Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke as Mana Whenua and Mana Moana for Te Whakaraupō / Lyttelton Harbour.

Whaling at Waitata Little Port Cooper

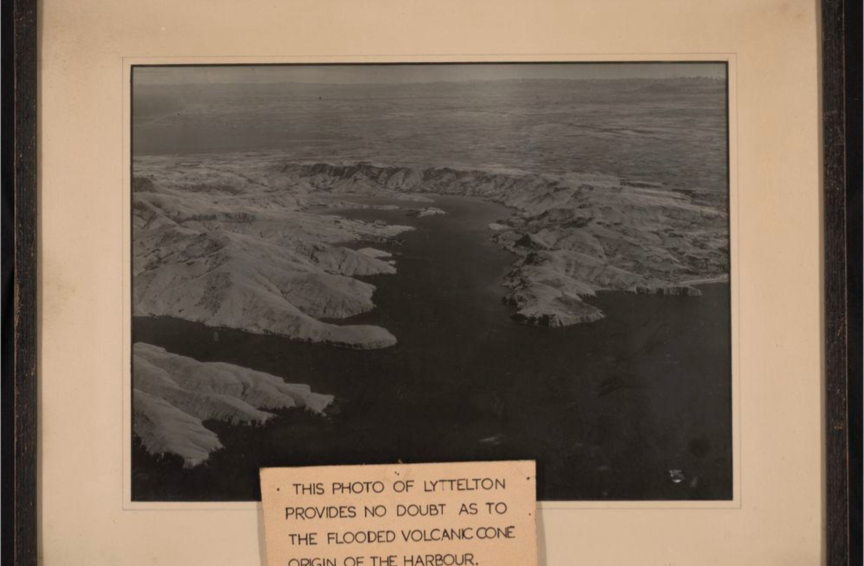

At the exposed mouth of Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour lies a small bay carved deeply into the steep cliffs below the southern headland of Te Piaka Adderley Head (Charles Adderley was an MP and prominent member of the Canterbury Association). Piaka refers to the edible root or bulb of raupō (bulrush) and therefore connects to the greater harbour's name of Whakaraupō (Lyttelton Harbour). Known to Māori as Waitata, the sheltered bay was utilised by residents of Ngāi Tahu's Puāri pā at Koukourārata Port Levy for gathering kaimoana.

The bay's first European name, Whalers Retreat, poetically evoked the earliest European activities in the region. Whaling had begun in Aotearoa's waters in the early 1790s with vessels crewed by tough men primarily from Britain, North America, Australia and France, many of whom were ex-convicts; hard men for certain. Their target for the lucrative blubber and baleen was the Southern right whale (Eubalaena glacialis australis), humpback, and sperm whales. All of these migrated along Aotearoa's long coastline to and from feeding grounds in the wild southern oceans to warmer breeding grounds. The right whale was so named as it was the ‘right’ one to target, being slower and more passive than other species and because mothers with calves would not desert their young; they were slaughtered first to ensure the capture of the frantic mother.

Whaling ships Lucy-Ann and Joseph Weller were probably the first to visit the bay in 1835. In 1836 Captain Hempleman's brig Bee spent about eight months taking refuge in the relatively sheltered waters of the bay. The crew used the beach for the odorous and often dangerous process of scarving and flensing the carcasses (when not using a shore station, these activities would take place with the whale hung by its tail alongside the ship). The blubber was then rendered to its valuable oily essence in trypots. Bone was sometimes buried in order to rot away the remaining flesh and huge tent-like piles of whalebones were left bleaching in the sun.

The headland was a prime vantage point to sight the telltale spouts of migrating cetaceans and to convey messages between shore, ship and whaleboat. At one time, as many as fourteen whaling ships were working the waters of Pegasus Bay from the cove. In July 1836 Captain Rhodes of the Australian abandoned seventeen crew ashore for mutiny, a common solution to discipline problems aboard ship. There had been numerous troubles on board until the final insubordination – the whalers had refused to row their longboat with whale in tow to shore from a mere 40 kilometres out at sea!

Later, John Ames operated a shore whaling station through 1844-1845, despite the industry's focus having moved to more profitable waters as right whale numbers became decimated. According to the journal of Asia's surgeon, Dr Felix Maynard, trypots, boilers, furnaces and all manner of gear were thrown out into the depths of the bay's waters when that ship departed for good, leaving little evidence but whale bone of the gruesome use of the cove.

By the 1840s, Whalers Retreat was widely referred to by the English name that is known today; Little Port Cooper – a 'little sibling' to the larger Port Cooper (which became Port Lyttelton in 1857) in which it lies. The name was bestowed by Captain William Wiseman of the brig Elizabeth in honour of his employer Daniel Cooper. Cooper, originally from Lancashire, was a former convict transported to the Australian penal colony for life, who became a wealthy and successful sealer, trader and ship merchant in Sydney. His partner and fellow ex-convict, Solomon Levey, (transported for the theft of 90 pounds of tea and a chest), also left his mark on history in the name of neighbouring Port Levy, albeit without the second ‘e’ in his surname.

See also Mary Stapylton-Smith's “The Other End of the Harbour”, 1990, Hazard Press